Human-Centered Design: Innovating With and For Marginalized Populations

by Web Administrator | September 9, 2010

Tackling entrenched oppression through access to education

Reboot helps UNICEF work to empower Suriname’s long marginalized indigenous communities

Problem:

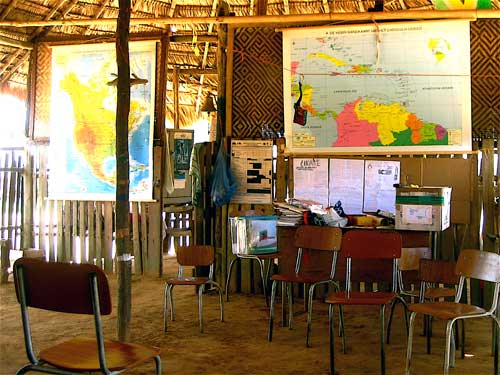

The indigenous tribes of Suriname face great discrimination. Living in scattered, remote villages in the jungle interior, they lack access to basic services and are politically and economically marginalized. Across various developmental and social indicators, the indigenous populations fall below the national average. In recent years, the tribal communities’ already difficult way of life is being further threatened as mining companies continue heavy excavation on their resource-rich homelands. Largely ignored by the central government, the indigenous communities have no redress, despite petitioning international bodies.

Our Approach:

Results:

- See the full case study below. -

Problem

The indigenous tribes of Suriname face great discrimination. Living in scattered, remote villages in the jungle interior, they lack access to basic services and are politically and economically marginalized. Across various developmental and social indicators, the indigenous populations fall below the national average. In recent years, the tribal communities’ already difficult way of life is being further threatened as rich mineral deposits have been found in their native lands. The resources have attracted foreign mining companies often unconcerned about the well-being of tribal communities. Largely ignored by the central government, the indigenous communities have no redress, despite petitioning international bodies.

How to empower the tribal communities to protect their interests in the face of such challenges? One path is through access to information and education, the means to self-organize. Yet education in the interior is dismal and interest in education is low. Though primary education is formally free, schools in the interior still collect fees, which are prohibitively high for most families and there is little opportunity for academic advancement post-secondary. In the capital, Paramaribo, over 76 percent of children finish primary school yet the estimated average in some rural regions is as low as 7 percent.

Complicating Factors.

- The primary education curriculum has not changed since 1975; thus, in addition to being irrelevant for the tribal communities, it’s irrelevant for today’s world. Curriculum reform, however, is highly politically charged and culturally sensitive issue, that requires government support and significant time and resource investment.

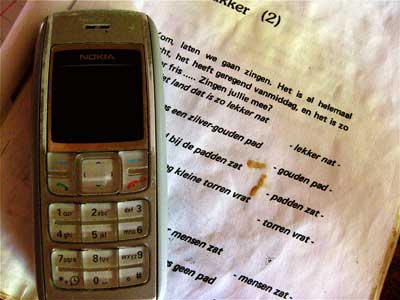

- Children are unable to communicate with their teachers – who are largely from the coastal cities – and vice versa. The languages of instruction are the two national languages: Dutch (the former colonial language) and Sranantongo (the lingua franca of the coastal cities), but most in the interior speak only tribal tongues.

- Teachers in the interior often don’t show up for school: Oftentimes, they either take extended ‘sick leave’ to go the city or simply don’t show up for class. Most teachers in the interior are there against their will – they feel unappreciated and isolated. Though they may abandon their students for long stretches, their negligence bears no consequences.

- Dependence on foreigners: Many tribal communities rely on the largesse of NGOs to provide basic services and essential items for them.

- Inherent disincentives for education reform within government: Roughly 40 percent of Suriname’s work force is employed by the public sector, thus many families benefit from ineffective system – even if they themselves do not work in the education sector, their family or friends might.

Analysis

To participate in the systems and decision processes that affect their lives, people need relevant, timely information on the issues at stake. To protect their interests, people require the facilities to calculate, preserve and express their ideas, and in a manner understood by those that affect their livelihoods. The dire state of education in rural Suriname debilitates the country’s most marginalized, effectively taking away their agency and ability to protect their rights. The effects will be devastating for the most vulnerable populations, especially as commercial and political influences expand in the interior.

Our Approach

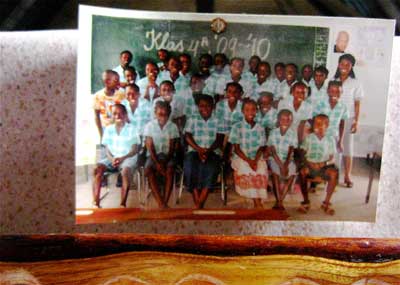

We led a three-week field study in Suriname covering seven of the most remote tribal villages in inland Suriname. The research team we assembled consisted of experts in design research, international development, ICT4D, and software development, as well as UNICEF Suriname staff – including the Country Representative, the head of the office – and local NGO partners. This was to ensure greater understanding of the challenges in the interior by those who would be developing, administering, and advocating for new programming.

We sought to understand the challenges faced by all individuals in and around the education system – from frustrated heads of schools to indifferent parents to children of all attitudes towards schooling. The research focused on individuals, the analysis focused on the system – we tried to understand how people’s motivations and challenges created the current educational system that existed today, and the role each individual’s needs and aspirations played in an inclusive, equitable future.

We spoke with educators, teachers, parents, children in both structured and ad hoc formats; in groups and solo; in schools and in the streets. In addition, we met with representatives from the Surinamese Ministry of Education to help secure local government buy-in and support, and with representatives from local institutions who might help develop and manage the reform process.

Based on the field data, we identified opportunity areas for supporting rural education. Seeking outside expertise, we partnered with NYU’s Steinhardt School of Culture, Education, and Human Development, and education expert Dr. Christopher Hoadley. The team – based across the US and in Suriname – set to work brainstorming possible solutions. Proposals ranged from a mobile learning centre that would float through the rivers of the jungle to a Next Surinamese Top Teacher radio program – inspired by an American television show about fashion models – all developed explicitly for Suriname’s unique challenges. This was an intensely generative and rapidly iterative process – each iteration was presented to various stakeholders for feedback, with the next round building upon the feedback.

Results

Moving forward from the above work, UNICEF Suriname is developing a network of community knowledge banks with ‘dumphone’ integration to deploy to 250 villages in rural inland Suriname. Each bank – both the system and the program around it – will be customized based on the needs of the particular village.

Both children and adults will be able to create, edit, rate and access information that has been customised for them; develop engaging personal connections around topics they are interested in; and search for information to assist them in their day-to-day lives. Though built on sophisticated hardware and software, the system will be practical and intuitive for its users. This will encourage rural communities to experiment and learn with minimal external input, itself an empowering process.

Highly configurable and widely practical, the platform will integrate with existing UNICEF programs to improve efficiencies and expand reach, and the infrastructure will lay the foundation for future initiatives wanting to leverage technological opportunities.

Access to locally generated knowledge will build community interest around learning, as children and young people will be able to seek and find information about matters that are relevant to them. Community members will be able to contribute knowledge for communal gain and be recognized for their contributions, thus starting a movement around community information building and sharing.

Beyond meeting the initial mandate, other concepts have come out of the research. Other potential programs currently in development include:

- A framework for real-time, regular and ongoing school and teacher assessment to increase accountability, and an alternative incentive structure based on these assessments.

- An indigenous cultural preservation program that allows communities to document and preserve indigenous cultural, historical, health and environmental knowledge. In partnership with the National Archive, this would also empower communities by allowing them to tell their stories in their own words and motivate them to learn new technologies as the program would demonstrate an immediate relevance of technology in their daily lives.

- Training in knowledge and skills for teachers, especially in language skills to ensure they are comfortable in the communities to which they are deployed and able to communicate with their students. And support networks for teachers to decrease feelings of isolation and to increase morale.

- A supplementary curriculum program that allows students to co-create meaningful, relevant content that is then integrated into the national curriculum.

- A second-chance education program for youth that have dropped out to enhance basic literacy, numeracy, and vocational skills

- Programs from UNICEF’s HIV/AIDS team to deliver content and provide interactive support for children around sexually transmitted infections and HIV/AIDS.

Development will be done in close partnerships with local communities. As a measure of local demand, and to ensure community buy-in and ownership, each village will be required to contribute to the process of technical system installation, through labour and/or nominal financial contributions. This approach was novel to UNICEF and encountered some resistance at first, but once rationale was explained, UNICEF agreed to adopt this strategy

The impact of this program will grow with the communities’ increased familiarity with and usage of the technical platforms and with the maturation of the ICT sector in Suriname. UNICEF’s proposed technical system – which runs on flexible open-source platforms – will allow the rural communities to adapt to and take advantage of anticipated, latent ICT opportunities.